(The photos below were taken in Hope Cemetery, Worcester, unless otherwise labelled.)

I’ve always been

drawn to explore cemeteries, especially when I travel. And I love photographing monuments and gravestones.

Often the words on the stone are intriguing-- clues to a cryptic but dramatic

story.

A cemetery in Minster Lovell, Gloucestershire, England

My kids would

probably attribute my love of cemeteries to my morbid streak, but I disagree—I

love cemeteries because they are filled with testaments of love as well as hope

for a future reunion with the departed. Lovingly tended graves are a physical pledge:

“You are not forgotten. You live in my

heart.”

So it’s no

wonder that, for a photojournalism course I took last year at the Worcester Art

Museum with photographer Norm Eggert, I chose for my project photos taken over

many visits to Hope Cemetery in Worcester.

I posted some of

those photos on Dec. 3, 2012, in “A Cemetery Called Hope.” I began the essay this way: “Hope

Cemetery is the place where my body will be buried. I like visiting and

photographing cemeteries because they’re filled with virtual symbols of love,

expressed in the words engraved on the stones, the flowers, candles, flags, toys,

burning incense, balloons, statues, birthday cakes, prayers,

rosaries, letters, even bottles of whiskey and un-smoked cigarettes left

by visitors on the graves.

“All

these things are an expression of the hope that one day we may be reunited with

our departed loved ones. No one knows if that’s true, but that’s why

‘Hope’ is an appropriate name for a cemetery.”

Over the years, I‘ve

visited beautiful and incredibly moving cemeteries in many countries. Some that stand out in memory include the

“City of the Dead” in Glasgow, Scotland; the famous “Pere Lachaise” in Paris

(where I saw a mourner pour a whole bottle of Scotch on the grave of Jim

Morrison—and I was enchanted by the monument to Heloise and Abelard—the nun and

the philosopher/monk, apart in life but together forever in death.)

Heloise and Abelard, Pere Lachaise, Paris

One of my favorite

cemeteries, which I happened on by chance, is the “poor people’s cemetery” on

the island of Martinique, where each grave—every one of them homemade-- looks

like a little house with a photograph of the deceased over the door.

Day of the Dead poster, Oaxaca, on my studio wall

The ultimate

cemetery experience is staying up all night in Mexican cemeteries during the

Day of the Dead celebrations. I’ve had

that privilege as a member of chef Susana Trilling’s “Dias de Muertos” cooking adventures in

Oaxaca.(See “Seasons of My Heart” for a list of all her culinary tours.)

The Mexicans have a much more comfortable relationship with death than we do in the United States. On the days of the dead (children are believed to return on October 31, adults the following day)—the surviving family members decorate the graves with flowers, candles and (often) elaborate sand paintings and then settle in to spend the night and welcome visitors with food, music, beer and whatever else the dead person liked in life. The whole holiday resembles a fiesta more than a funeral.

Of course I take

photos when I’m visiting a cemetery, and often I’m photographing and weeping at

the same time. Most graves don’t make me

cry, and some make me laugh, like the one that showed the deceased posing with

his favorite cockfighting rooster.

But when I see

an elderly person talking to a gravestone, and especially when I see the stone

of a young child who barely tasted life, but whose grave is decorated at every

season by parents who never stopped mourning—that’s when I start crying.

At Hope Cemetery

I was frequently brought to tears by the small, flat gravestones in the “Garden

of the Innocents” where the city of Worcester will pay for the burial of

infants and children whose parents can’t afford a plot and gravestone.

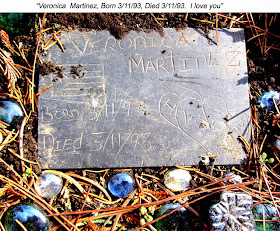

Most touching of

all the small stones, where parents leave toys and holiday decorations, was

this one where the parents carved the message by hand:

Given my

penchant for photographing cemeteries, it was a sure thing that I would sign up

for a class at the Worcester Art Museum that takes place next Friday, led by my

friend, photographer Mari Seder. All

day, from 10 a.m. to 4 p.m., we will be photographing in Worcester’s Rural

cemetery—within walking distance of the Museum—with a break for a picnic

lunch. I’ve heard that Rural Cemetery is

even older and more picturesque than Hope Cemetery, and I’ve been wanting to

visit it; an experience which will be even better with Mari’s guidance and photographer’s eye.

Mari is a prize- winning photographer who

spends half the year living in Worcester and the other half in Oaxaca, Mexico,

where she’s had exhibits of her stunning photographs of Mexican women and their

household altars. Here’s a photograph

she took of the grave of a 12-year-old Mexican girl, Juanita Velasquez Cruz,

who lived from 1890 to 1902.

I’ve already traveled

to Oaxaca twice for the classes that Mari offers there in photography, painting

and collage, and once I got to tag along with her to photograph in Puebla,

as well, where the Indian-decorated

churches of Cholula, virtually encrusted with zillions of folk art angels, blew

my mind. You can see them on my blog

post “Angels in the Architecture”.

Mari’s day-long class at Rural Cemetery on

Friday is part of a new series of immersion classes offered by WAM that allows

students to spend an entire day with regional artists in an intensive day-long

class in each artist’s speciality, learning their secrets and getting face time

with these experts in the fields of photography, collage, illustration or Celtic

art.

Now that fall colors are burnishing the

trees, I’m hoping for some remarkable photographs to come out of Rural Cemetery

this Friday. Stay tuned.

I love walking through cemeteries and looking at the carvings on the headstones. My family thinks I'm a ghoul, but I love the art, symbolism, and history found on the stones

ReplyDeleteUn cambio en el modo de vida puede ser de mucha ayuda.

ReplyDelete