Antique photographs of American slaves have been much in the news lately. Three days ago, on March 21, the front page of The New York Times featured an article and a large image of a black slave named Renty, naked from the waist up--one of seven slaves who in 1850 were forced by Harvard scientist Louis Agassiz to be stripped and photographed as documentation for his theory that blacks and whites were descended from different origins and that black people were inferior. The Times ran the article because a woman who believes she is descended from Renty has filed suit against Harvard, demanding that two of the 15 large daguerreotypes are rightfully hers. Today, March 23, The Times ran a follow-up article debating the question: who owns the rights to a photograph and to artifacts of African American history?

Earlier, on March 7, New York Times reporter Maurice Berger reviewed the book "Girl in Black and White" by Jessie Morgan-Owens, about a seven-year-old slave girl named Mary who appeared to be so white that Abolitionists in Massachusetts, led by Charles Sumner, bought her freedom, brought her up north and had her photographed in 1855, so that Sumner could circulate to important politicians and newspapers her image, intended to shock them that such a white-appearing child could be a slave.

From its very beginnings in 1839, photography has proved to be a potent propaganda weapon, used by both abolitionists and white supremacists to touch peoples' emotions and win support for their cause. I've been collecting vintage, historic photographs for some 40 years and writing about them on this blog since 2009, often discussing images that have to do with race. Today I'm re-posting an essay from March 7, 2012, in which I discuss the background of the Harvard dags. In my next post I will talk about my daguerreotype of the little white-appearing slave girl who was photographed by Sumner and became the "poster girl" of the abolitionist cause.

In my previous post,

I discussed the recently-in-the-news photos of the “White Slave

Children of New Orleans” which portrayed only white-appearing slave

children, not black ones. I

explained how this apparently wrong-minded and politically incorrect

practice of the Abolitionists had originated nearly a decade earlier

with a daguerreotype of a white-skinned little girl named Mary Botts. She

was purchased and brought north by her father (an escaped slave) with

the help of Senator Charles Sumner of Massachusetts who paraded her (and

circulated her photographic image) around New England making her a celebrity described in The New York Times and other media.

In 1855, Sumner may have been the first to focus on white-appearing slaves to raise indignation against the practice of slavery. It

worked so well that, after Lincoln’s emancipation proclamation of Jan.

1, 1863, Northerners and Abolitionists who wanted to support schools for

former slaves went to New Orleans looking for white slave children to

bring up north and photograph. According to Celia Caust-Ellenbogen of Swarthmore College,

“Keeping these schools up and running would require ongoing financial

support. Toward this end, the National Freedman’s Association, in

collaboration with the American Missionary Association and interested

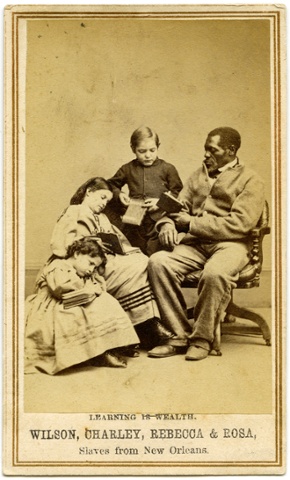

officers of the Union Army launched a new propaganda campaign. Five children and three adults, all former slaves from New Orleans, were sent to the North on a publicity tour.

A full page of Harper’s Weekly’s Jan. 30, 1864 issue was devoted to this

engraving, which was based on a large-format photograph taken of the

group. Explaining the picture was a letter written by C.C. Leigh introducing the stars of the new propaganda campaign. Pay attention to how he keeps emphasizing the intelligence of the children.

“To the Editor of Harper’s Weekly:

The group of emancipated slaves

whose portraits I send you were brought by Colonel Hanks and Mr. Philip

Bacon from New Orleans, where they were set free by General

Butler…REBECCA HUGER is eleven years old, and was a slave in her

father’s house, the special attendant of a girl a little older than

herself. To all appearance she is perfectly white. Her complexion, hair and features show not the slightest trace of Negro blood. In

the few months during which she has been at school she has learned to

read well, and writes as neatly as most children of her age. Her

mother and grandmother live in New Orleans, where they support

themselves comfortably by their own labor…ROSINA DOWNS is not quite

seven years old. She is a fair child, with blonde complexion and silky hair. Her father is in the rebel army. She has one sister as white as herself and three brothers who are darker. Her mother, a bright mulatto, lives in New Orleans in a poor hut, and has hard work to support her family. CHARLES TAYLOR is eight years old. His complexion is very fair, his hair light and silky. Three out of five boys in any school in New York are darker than he. Yet this white boy, with his mother, as he declares, has been twice sold as a slave. First by his father and “owner”, Alexander Wethers, of Lewis County, Virginia, to a slave trader named Harrison, who sold them to Mr.Thornhill of New Orleans. This

man fled at the approach of our army and his slaves were liberated by

General Butler. The boy is decidedly intelligent, and though he has been

at school less than a year, he reads and writes very well. …”

The letter goes on to describe the adults in the group—two of them

chosen, evidently, because they had physical scars from their masters’

mistreatment. Wilson Chinn, on

the left, was branded on his forehead by Volsey B Marmillion, who

branded all his 210 slaves, and Mary Johnson carried the scars of 50

cuts on her arms and back –given by her master because one morning she

was “half an hour behind time in bringing up his five o’clock cup of

coffee”.

The little girl on the left next to Charley was described as AUGUSTA BROUJEY, nine years old. “Her

mother, who is almost white, was owned by her half-brother, named

Solamon, who still retains two of her children. ISAAC WHITE is a black

boy of eight years; but none the less intelligent than his whiter

companions. He has been in school about seven months, and I venture to

say that not one boy in fifty would have made as much improvement in

that space of time.”

The man on the far right is “the

Reverend Mr. Whitehead” who managed to earn enough as a house and ship

painter to buy his freedom and is described thus: “The reverend

gentleman can read and write well and is a very stirring speaker. Just now he belongs to the church militant, having enlisted in the United States Army.”

The letter in Harper’s ends by telling where the small CDVs of the

individuals can be bought for 25 cents each or the large photo of the

whole group for one dollar. This

would have been a very good investment, for today the individual CDV’s

can cost several hundred dollars or more, and the only copy of the large

group photo that I have ever seen was in the collection of the

Metropolitan Museum.

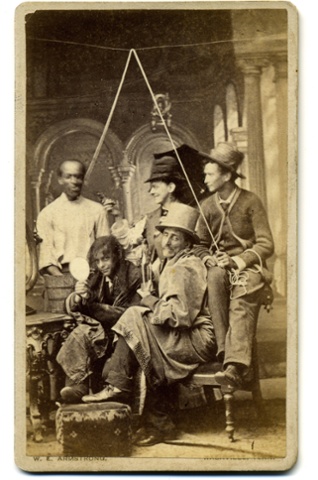

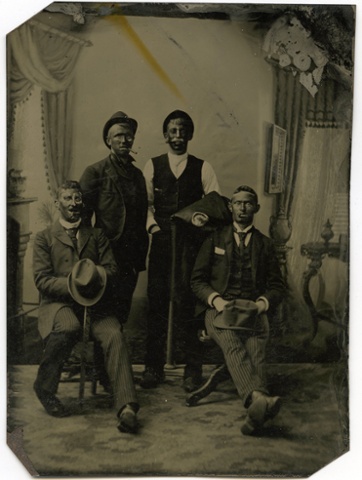

Three photographers took photos of the white slave children: Charles Paxson and M. H. Kimball in

New York, and J.E. McClees in Philadelphia (where they were kicked out

of their hotel when the manager learned they were not “really” white.)

The children were dressed in elegant clothing and posed with props—the

American flag, an ornate mirror, books which they were studying—to

appeal to the sentimentality of Victorian audiences. (See my previous post.) Kimball produced the most “shocking” photo (to Victorian eyes) of dark-skinned Isaac and white-skinned Rosa arm in arm . (Augusta was in only 2 of the 22 photos on record and Isaac in three, but Rosa and Rebecca are pictured in most of them.)

The most photographed and most popular of the “white slave children” was

Rebecca, 11 years old, posed in ever more stylish outfits. Prof.

Mary Niall Mitchell suggests in an essay “Rosebloom

and Pure White” in American Quarterly, Sept. 2002, that Rebecca fascinated the Victorians because she was closest to becoming an adult woman and the thought of her sexual vulnerability —a white slave girl who could be bought and sold and raped—fascinated and horrified the Northerners. Clearly the white children were the result of masters raping the slave women who were their property. Professor Mitchell repeats the famous quip of southern diarist Mary Chestnut:

“Every lady tells you who is the father of all the mulatto children in

everybody’s household, but those in her own she seems to think drop from

the clouds, or pretends so to think.”

Professor Mitchell writes in the same essay: “In

the images of Rosa and Rebecca, a notion about white little girls as

pure and precious things may have been employed to redeem those viewers

who had yet to rally around the antislavery cause and encourage them to

act on the girls’ behalf.”

Finally, the Abolitionists photographing the “white slave children” were using the new and undeniably “scientific” medium of photography to battle the beliefs of the leading scientist of the day—Louis Agassiz—famous Harvard natural scientist. He claimed and tried very hard to prove “scientifically” that the Black race was an inferior and separate biological species. According to Kathleen Collins in “Portraits of Slave Children” in “History of Photography”, July- September 1985, “The

anthropologist Stephen Jay Gould recently reconstructed Agassiz’ life

and thought from his unexpurgated letters in the Harvard University

Collection. Gould concluded

that behind Agassiz’ separate creation theories was an initial, visceral

reaction to contact with blacks, which left him with an intense

revulsion against the notion of miscegenation.”

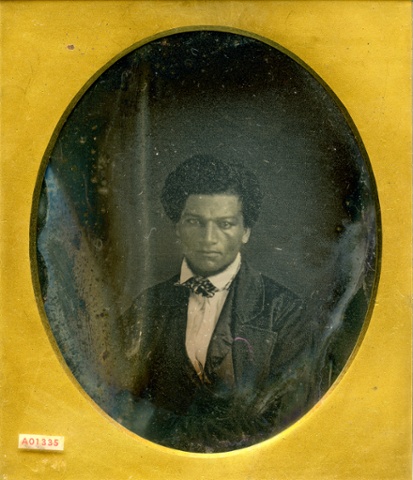

Agassiz himself tried to use the science of photography to promote his

theories that blacks were a different species from whites. Long before the civil war, he toured Southern plantations and had the owners bring forth the most “African” looking slaves. In

1850 Agassiz arranged for J. T. Zealy, a daguerrotypist in Columbia,

South Carolina, to take photographs of African-born slaves from

plantations Agassiz had visited.

The slaves were stripped and photographed and these haunting daguerreotypes were sent to Agassiz at Harvard. In

1976 they were found in a storage cabinet at the Peabody Museum of

Archeology and Ethnology. (To see these dags and read a brilliant

discussion of Agassiz’s racism and his use of the camera to debase his

subjects, go to http://usslave.blogspot.com/2011/10/black-bodies-white-science-louis.html. ) Here are two of the captions:

The

Zealy pictures reveal the social convention which ranks blacks as

inferior beings, which violates civilized decorum, which strips men and

women of the right to cover their genitalia. And yet the pictures

shatter that mold by allowing the eyes of Delia and the others to speak

directly to ours, in an appeal to a shared humanity.

Agassiz

commissioned these images to use as scientific visual evidence to prove

the physical difference between white Europeans and black Africans. The

primary goal was to prove the racial superiority of the white race. The

photographs were also meant to serve as evidence for his theory of

“separate creation,” which contends that each race originated as a

separate species.

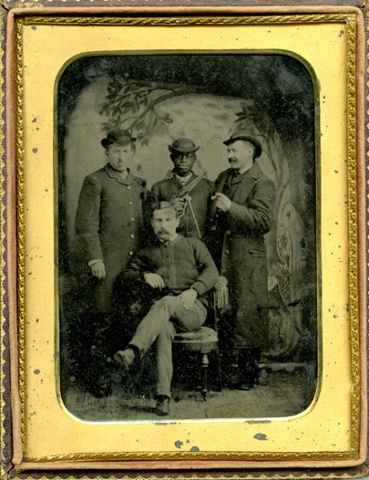

So the Abolitionists who photographed the white (mulatto) children of

New Orleans, arm in arm with a black slave child, and who emphasized at

every turn the intelligence and good behavior of these children, were

fighting fire with fire—using the new science of photography to refute

visually the beliefs of the country’s most famous scientist and other

racists who insisted that the two races should not and could not be

mixed.