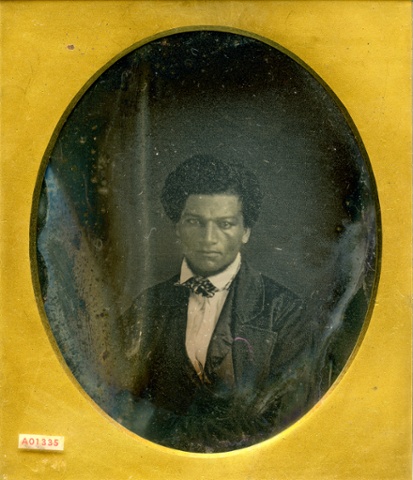

On March 12, W. W. Norton published "Girl in Black and White", subtitled "The Story of Mary Mildred Williams and the Abolition Movement", by Jessie Morgan-Owens, a professional photographer, scholar, Phd. and the dean of studies at Bard Early College in New Orleans. In the book, Jessie mentions how she and I met in Worcester in 2013, while she was in residence at the American Antiquarian Society researching Mary's life, so that she could see my daguerreotype of the little girl who became the face of the Abolition movement. In 1855, Mary was displayed on stage, taken to newspaper offices and her photograph was circulated to politicians and VIPs by Senator Charles Sumner--after Sumner and her escaped father and abolitionists in Massachusetts, including Longfellow and Thoreau, raised enough money to buy freedom for Mary and the rest of her family.

The reason Sumner was eager to display the girl was because she appeared to be white, but was born into slavery. Jessie, in her book, decided to call the girl "Mary Mildred Williams" because "Williams" was the alias the girl's father chose when he escaped from Virginia and his daughter adopted it when she grew up. I call her "Mary Botts"--her slave name--in the essay below, because that's the name I first discovered ten years ago, while researching the identity of the girl in my dag. Many abolitionists and reporters called her "Little Ida May"--the name of a fictitious child in a hugely best-selling novel, published in 1854, about a white girl who is kidnapped, beaten and sold into slavery, suffering much until her father saves her.

The reason Sumner was eager to display the girl was because she appeared to be white, but was born into slavery. Jessie, in her book, decided to call the girl "Mary Mildred Williams" because "Williams" was the alias the girl's father chose when he escaped from Virginia and his daughter adopted it when she grew up. I call her "Mary Botts"--her slave name--in the essay below, because that's the name I first discovered ten years ago, while researching the identity of the girl in my dag. Many abolitionists and reporters called her "Little Ida May"--the name of a fictitious child in a hugely best-selling novel, published in 1854, about a white girl who is kidnapped, beaten and sold into slavery, suffering much until her father saves her.

When I

began collecting antique photographs about thirty years ago, I started out buying everything I could find. Then I began to specialize, gravitating toward early images

of children, twins (which I wrote about in a April 29, 2010 blog post:

“Diane Arbus and Spooky Twins”) and photographs reflecting attitudes

toward race and slavery. (For example, I wrote about the image of “The Scarred Back of a Slave Named Gordon” in a post dated Oct. 2, 2009. My information about that image was also printed in the New York Times book review of Oct. 4, 2009). This image was also widely circulated by abolitionists. My copy of it, below, is a hand-colored glass negative of the original black and white photo, probably meant to be projected in a "magic lantern.")

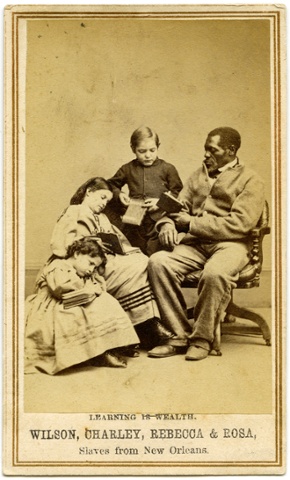

While

collecting slave photographs, I became fascinated with the “white slave

children of Louisiana” as I call the series of CDV (carte-de-visite)

photos of freed children from New Orleans who appear to be completely

white. These small, cardboard-mounted photos were sold in great

quantities by abolitionists during the Civil War. On the back of each photo was printed: “The

nett [sic] proceeds from the sale of these Photographs will be devoted

to the education of colored people in the Department of the Gulf, now

under the command of Maj. Gen. Banks.”

I had so many questions about these CDVs. First,

why did the abolitionists go down to the schools of freed slaves in New

Orleans and pull out only those who appeared to be white, then send the

children up to New York and Philadelphia to be dressed in fine clothes

and posed in sentimental scenes for photos to sell? Why

did black-appearing children not get chosen for this? And how did these

former slave children feel about being taken away from their mothers,

paraded up north for the media like zoo animals and then sent back down

South? (They even got kicked out of their hotel in Philadelphia when the owner discovered they weren’t “really” white.)

Through

research, I’ve learned the answers to some of these questions about the

Louisiana CDVs, but today I’m only focusing on one photograph that was made, in 1855, about nine years before the Civil War CDVs. It’s a ninth-plate daguerreotype that I bought on E-Bay in 2000 of a little girl in a plaid dress .

The seller, from Tennessee, included with this cased image information on where it was found. “This…photograph was purchased at Headley’s Auction in Winchester VA, July 1997. It came…out of the “Ashgrove” estate in Vienna, VA. The house originated as a hunting lodge in 1740 …and was sold to James Sherman in 1850, who would never own or hire a slave. He died in 1865 and passed it to his son, Capt. Franklin Sherman, Tenth Mich. Cavalry. Capt

Sherman’s wife Caroline (Alvord, a native of Mass.) came to the country

in 1865 to teach the children of the newly freed slaves.”

The most

intriguing thing about this daguerreotype, of course, was the faded

inch-square piece of paper glued to the back of the case upon which

someone has printed “Mulatto raised by Charles Sumner”. I put

this image aside in 2000 along with the papers the buyer had sent me

about the Ashford plantation, and forgot all about them.

Then, in November 2010, I had a visit from Greg Fried, a professor at Suffolk University in Boston who wanted to scan some of my photographs for a new web site he was preparing called “Mirror of Race” (www.mirrorofrace.org.) I showed him the Louisiana CDVs and the daguerreotype of the “Sumner-raised” child. After he left, I went on Google and typed in the words “Charles Sumner” and “slave”. I discovered a short article from the New York Times dated March 9, 1855, which read:

A

WHITE SLAVE FROM VIRGINIA. We received a visit yesterday from an

interesting little girl, — who, less than a month since, was a slave

belonging to Judge NEAL, of Alexandria, Va. Our readers will remember

that we lately published a letter, addressed by Hon. CHARLES SUMNER, to

some friends in Boston, accompanying a daguerreotype which that

gentleman had forwarded to his friends in this city, and which he

described as the portrait of a real "Ida May," — a young female slave,

so white as to defy the acutest judge to detect in her features,

complexion, hair, or general appearance, the slightest trace of Negro

blood. It was this child that visited our office, accompanied by CHARLES

H. BRAINARD, in whose care she was placed by Mr. SUMNER, for

transmission to Boston. Her history is briefly as follows: Her name is

MARY MILDRED BOTTS; her father escaped from the estate of Judge NEAL,

Alexandria, six years ago and took refuge in Boston. Two years since he

purchased his freedom for $600, his wife and three children being still

in bondage. The good feeling of his Boston friends induced them to

subscribe for the purchase of his family, and three weeks since, through

the agency of Hon. CHARLES SUMNER, the purchase was effected, $800

being paid for the family. They created quite a sensation in Washington,

and were provided with a passage in the first class cars in their

journey to this city, whence they took their way last evening by the

Fall River route to Boston. The child was exhibited yesterday to many

prominent individuals in the City, and the general sentiment, in which

we fully concur, was one of astonishment that she should ever have been

held a slave. She was one of the fairest and most indisputable white

children that we have ever seen.

This discovery got my adrenaline going. I googled “Mary Mildred Botts” and learned that the white-appearing slave child who was admired by The New York Times was discussed in a 2008 book called “Raising

Freedom’s Child—Black Children and Visions of the Future after

Slavery,” written by a University of New Orleans professor, Mary Niall

Mitchell, who (small world!) was someone I had communicated with six

years before while trying to research the Louisiana CDV’s. I immediately ordered the book from Amazon.

When it arrived, I was stunned to find on page 73 a photo of Mary Botts that was the mirror image of MY dag. (The one in the book--also on the cover of Jessie's book) is from the collection of the Massachusetts Historical Society.) Prof. Mitchell gave more explanation about why this young girl was photographed and brought north by Charles Sumner.

“By

the eve of the Civil War, abolitionists recognized the potential of

white-looking children for stirring up antislavery sentiment…Although it

was the image of a raggedy, motherless Topsy that viewers might have

expected to see in a photograph of a slave girl, it was the “innocent”,

“pure,” and “well-loved” white child who appeared, a child who needed

the protection of the northern white public.

“The sponsors of seven-year-old Mary Mildred Botts, a freed child from Virginia, may have been the first to capitalize on these ideas, as early as 1855. Her

story also marks the beginning of efforts to use photography (in Mary

Botts’s case, the daguerreotype, as the carte-de-visite format was not

yet available) in the service of raising sentiment and support for the

abolitionist cause. (bold-facing mine.)

“…In his own characterization of Mary Botts,” Mitchell continues, “Sumner set a pattern that other abolitionists would follow. In

a letter printed in both the Boston Telegraph and the New York Daily

Times, he compared Mary Botts to a fictional white girl who had been

kidnapped and enslaved, the protagonist in Mary Hayden Pike’s

antislavery novel Ida May: ‘She

is bright and intelligent—another Ida May,’ [Sumner wrote] ‘I think her

presence among us (in Boston) will be more effective than any speech I

can make.’”

This

comparison of Mary Botts to the fictional kidnapped white girl worked

well for Sumner and the Abolitionists and made the little freed slave

quite a local celebrity. Prof. Mitchell quotes the diary of a Quaker woman named Hannah Marsh Inman who saw Mary Botts at a meeting house in Worcester, MA (which happens to be where I live now). On March 1, 1855, Hannah wrote: “Evening all went to the soiree at the Hall. Little Ida May, the white slave was there from Boston.”

Sumner realized that he was on to a good thing and circulated daguerreotypes of the child to prove her whiteness to those who might doubt. (Keep

in mind—the daguerreotype process was the first one ever made

available—by Daguerre in 1839-- and the images “written by the sun” on

the silvered copper plate were considered undeniable scientific proof of

the sitter’s appearance.)

Sumner

passed a daguerreotype of Mary Botts around the Massachusetts State

Legislature “as an illustration of slavery” and sent one to John. A.

Andrews, the governor of Massachusetts.(And Jessie, in her book, on page 133, traces the journey of MY dag from the home of an Abolitionist Massachusetts state senator to his daughter, who moved to Virginia to teach newly emancipated slaves. My dag stayed in the Ash Grove estate for 132 years until a woman from Tennessee bought it at auction, then offered it for sale in 2000, and it came to me in North Grafton, MA, coming full circle back to where it started.)

Only a year after parading Mary Botts through New York, Boston and Worcester and dubbing her “The real Ida May”, Charles Sumner’s devout abolitionist views led him to a crippling disaster, when, in 1856, he was so badly beaten on the floor of the Senate by South Carolina Representative Preston Brooks, who broke a cane over his head, that it would take years of therapy before Sumner could return to the Senate.

As

soon as I realized in 2010 that my dag of Mary Botts was one of the images used

by Sumner himself to advance the abolitionist cause, I got into an

excited e-mail correspondence with Professor

Mitchell, and Prof. Greg Fried,

who pointed out something I’d forgotten: an advertising card on the

back of my image showed that it was “Taken with the Double Camera For 25

Cents by Taber &; Co., successors to Tyler &; Co. Cor. Winter

&; Washington Sts. Boston”, while the mirror image belonging to the Massachusetts Historical Society was taken by Julian Vannerson, probably in Richmond, Virginia,

and seems sharper than mine, so mine must be a copy dag. (The only way

to copy a daguerreotype is to take a new daguerreotype of it. Each daguerreotype is one of a kind. Taber’s price of 25 cents sounds affordable, but at the time, the average working man made only about a dollar a day.)

On March 7, Maurice Berger, who writes the Lens column for The New York Times, discussed "Girl in Black And White", calling it "groundbreaking." He quoted Jessie Morgan Owens as saying, "Mary's daguerreotype was one of the first images of photographic propaganda and one of the first portraits made solely to prove a political point."

Personally, I'm very grateful to Jessie Morgan-Owens for her decades of work and research, which put flesh and blood into my daguerreotype. I'm thrilled to know that this image, taken in 1855, that is part of my collection, may represent one of the first efforts EVER to use the discovery of photography to touch people’s emotions and change their minds. This small image of a seven-year-old girl may be an example of the first time photography was used for propaganda, but it was certainly not the last.

Personally, I'm very grateful to Jessie Morgan-Owens for her decades of work and research, which put flesh and blood into my daguerreotype. I'm thrilled to know that this image, taken in 1855, that is part of my collection, may represent one of the first efforts EVER to use the discovery of photography to touch people’s emotions and change their minds. This small image of a seven-year-old girl may be an example of the first time photography was used for propaganda, but it was certainly not the last.